To view the original article and others visit the Cottage Shack magazine

As I have said before, being curator at the Coldwater Canadiana Heritage Museum (CCHM) afford me many unique experiences. From reading instructions on how to use a mechanical dog walker to mending a crazy quilt, there is never a dull moment. Through these articles I am able to share some of my wonderful experiences.

My previous article on the slaughterhouse was selected because it is my favourite building. But to me the most interesting display has to be the Godfrey beauty salon. This resides in our display barn, an old structure that, many years ago, was dismantled and re-erected on the museum property. When my school groups visit, I tell them that it is like going to the mall.

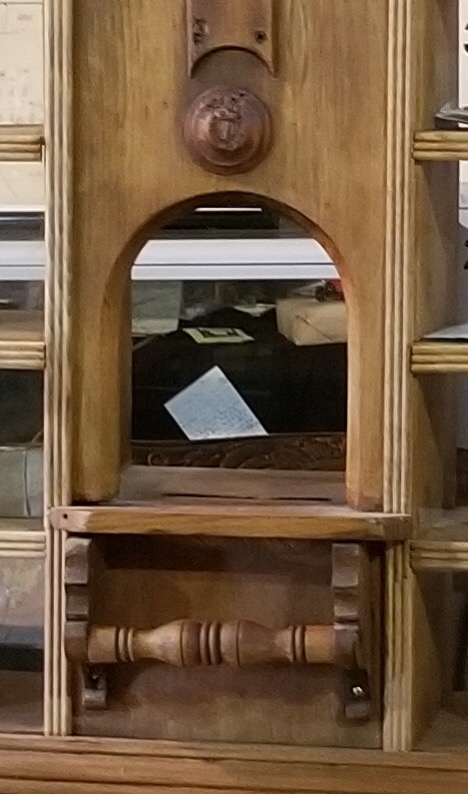

The display barn houses a cooper shop (barrel making), barber shop, post office, laundry, carpentry shop, magistrate’s office and a remarkable hair salon. Being all under one roof keeps the artifacts inside safe and dry. We have only to worry about the occasional rodent!

Many of our locals have fond memories of Velma and Ernie Godfrey’s popular shop. Shirley Janet, a local resident has also written about this beauty parlour for a local newspaper. She provided us with some wonderful insight into hairdressing of yore.

Velma Godfrey began hairdressing in high school, cutting neighbours hair for ten cents. She honed her skills at the Graham’s hair salon in Toronto prior to setting up shop on Bush Street, Coldwater in a home built by her grandfather. Her big move was to a boutique on Main Street in the Abbott block across from the Denison hotel.

Our research shows that almost 70 years ago a finger wave cost 35 cents and a shampoo 50 cents. Perms were $1.95 for short hair and $2.50 for long hair. That’s how it was before that special day when Velma purchased the dreaded Naturelle Crokinole permanent wave machine for a whopping $385. What an investment that would have been! The year was 1935 and many women preferred long hair styles with curls at the ends. “This machine was worth every penny,” said Mrs. Godfrey.

The first person known to get a “super” permanent was Mrs. Lyall Gray who paid five dollars for the honor. Word soon spread about this magical machine as Velma perfected the use of it. This marvellous invention permed hair in seven minuted and then needed three minuted to cool down. If it got unbearably hot a cooling blower helped to ease the discomfort.

Buisness was brisk, and in 1941 husband Ernie joined the Buisness. Shortly thereafter they moved the barbershop to rooms above Tipping’s Dry Goods Store. A barbershop is also replicated at CCHM and will be covered in a later article.

Even after the Naturelle Crokinole permanent wave machine became obsolete, Velma continued to use it – long after the introduction of much more compact units. More. Edna Cornell, a regular Customer, is reputed to have been the last customer attached to that infamous perm machine. Shortly after Ernie’s death, Velma retired from the business and many of the articles from her shop were lovingly donated to CCHM.

One very interesting item is an old-fashioned steamer used for scalp treatments. A mixture of coal oil and olive oil was heated to produce clouds of steam. The hairdresser would massage the head through holes on the sides of the rounded metal hood. Exactly how this was done is a bit of a mystery to us at the museum. If anyone of our readers recalls this gadget and can tell us how it was operated, we would be in your debt.

We also have a collection of hair curlers and crispers that look dangerous, to say the least. But they pale in comparison to the dreaded perm machine. It is by far the focal point of our little shop. One visiting lady asked me if it worked; I simply asked the lady if she would like to give it a go. Seeing how menacing it looks you can imagine her answer. Someday I might just be brave enough to plug it in.

My next article will continue with this hair care theme. This time the focus will be on barbering and the subject would be incomplete without the story of Loyd Bell who cut hair in Coldwater for 57 years. His barbershop and many of the tools of his trade are on display here at the Coldwater Canadiana Heritage Museum.

Come visit us when we reopen in the Spring and take a walk through our unique display barn.

by Patricia Turnour