To view the original article and others in the 2021 series, visit the Cottage Shack magazine online

“Afternoon tea…The mere clink of cups and saucers tunes the mind to happy repose.”

From the private papers of Henry Ryecroft, by George Gissin

My name is Patricia Turnour and I am Director and curator of the Coldwater Canadiana Heritage Museum (CCHM). Although we have closed things up for the winter, we have hopes and plans for next spring. One such custom we hope to preserve is our weekly Devon Tea. Due to Covid restrictions, we have certainly missed this event for the last two seasons.

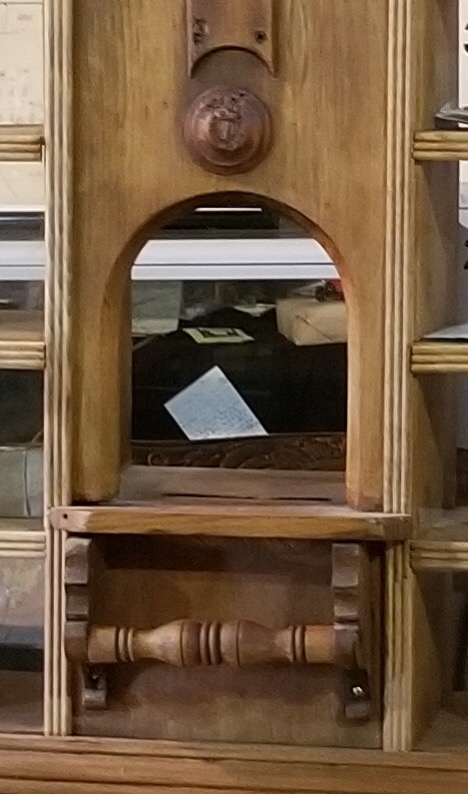

Since CCHM was established over 50 years ago, the house has been abuzz with many people every Wednesday afternoon. The cozy fireplace room is the perfect setting for an afternoon of relaxation and good company. Our volunteers and co-op students don period costumes and aprons to enhance the ambiance. A variety of teas and home-bakes scones with preserves are served in fine china at tables clothed in vintage linens. Children feel all grown up as they sip tea from our daily teacups. This weekly event soon became well known as the “Devon Cream Teas.”

The “Cream Tea” has a fascinating history rooted in British tradition. Food historian Matthew O’Callaghan found that teas became very popular in the 1840s just as tourism was beginning to flourish. Well-to-do ladies would often take train journeys into the countryside. There seemed to be something lacking between the mid-day and evening meals. Thus, late afternoon teas became very popular, filling this gap. They were relatively expensive and, therefore, out of the reach of most commoners. For the upper-class fancier fare such as sandwiches, fruit, ripened cheeses, dipped chocolate, crumpets and tea cookies were soon added. The more risqué was not for the tea-totalled, daring to add port, bourbon, sherry or even champagne to this afternoon delight. Eventually, afternoon tea became a staple of almost all British households.

The origin of Devon cream has even deeper roots in British history. When Tavistock’s Benedictine Abbey had been badly damaged by marauding Vikings in 997 AD, Ordulf, Earl of Devon oversaw repairs, and the monks rewarded the workers by feeding them bread, clotted cream and strawberry preserves. And so, the Devon cream tea was born. It was so well liked that the monks continued serving it to passing travellers. Unfortunately, the Abbey was destroyed in the 1500s but the legacy of its “clotted cream” lives on.

Another interesting anecdote comes from a long-standing controversy between Devon and Cornwall England. In Devon people first put the cream on their scones and then the jam. In Cornwall they put the jam on first. Queen Elizabeth apparently puts jam on first. When visiting CCHM and enjoying our Devon tea we will have you be the judge.

On many of these Wednesday afternoons artisans and craftsman are on the grounds demonstrating their skills. Some have product to sell.

All of our buildings are open and yours can be guided or self-guided using a map.

The schoolhouse is always open and with me as school mistress. Children are invited to experience the “pioneer school day” as we sing songs, play games and study the three Rs.

Local speakers are often available to talk about an activity that was popular in days gone by.

As one of our long-time volunteers has been quoted as saying: “Our teas are about keeping the past alive.” It is so important to preserve local history for future generations. These teas have also been an important social link to the community. Whether as a weekly volunteer or as a visitor from near or far, we welcome all our tea lovers to our cozy cabin.

See you in June! Tea is served.