To read the original article and others visit the Cottage Shack

My name is Clay and I am one of the original members of the A-team at Coldwater Canadiana Heritage Museum (CCHM). The A-Team is a group of dedicated volunteers who use their particular skills and experience to improve various aspects of the museum. On any given Wednesday you will see anywhere from six to twelve of us working on up to three different projects. These might, for example, include erecting a pole barn, restoring a buggy, installing a new roof, replacing old boards on a barn, adding signage, creating a kid-friendly playhouse, maintaining a steam-powered tractor. The list is endless.

Although there is a lot yet that needs doing of that we wish to accomplish, a truly amazing transformation is taking place at CCHM and we are proud to have a part in it. You could too!

In earlier stories of the A-Team, I wrote about volunteering at the museum on Wednesday mournings and about how our group was expanding. I also shared some details about the early restoration and refurbishment projects we tackled.

Over the winter of 2017/2018 we were blessed with the use of a large, well-equipped workshop that belongs to my brother-in-law. By this time the A-Team was working both mourning and afternoon of a Wednesday and had grown in size to six members, so we were able to tackle two projects. One was the pre-fabrication of the framing for a future storage shed and Playhouse for kids – it will be the subject of a future article.

The other project involved the restoration of an antique mail sorter donated by Tom and Terry Malloy who had obtained it about 15 years earlier in a Severn Township barn. It is a beauty. They had kept it high and dry in their basement throughout their tenure.

Sadly, they were unable to provide any knowledge about its origin. We chose to believe that it very likely had been employed in one of our local village post offices.

It’s fascinating that the modern postal system, having started with the inception of the adhesive postage stamp, came about in Canada mid-19th century around the time that pioneer Archibald Woodrow was building his homestead, the centrepiece of the museum.

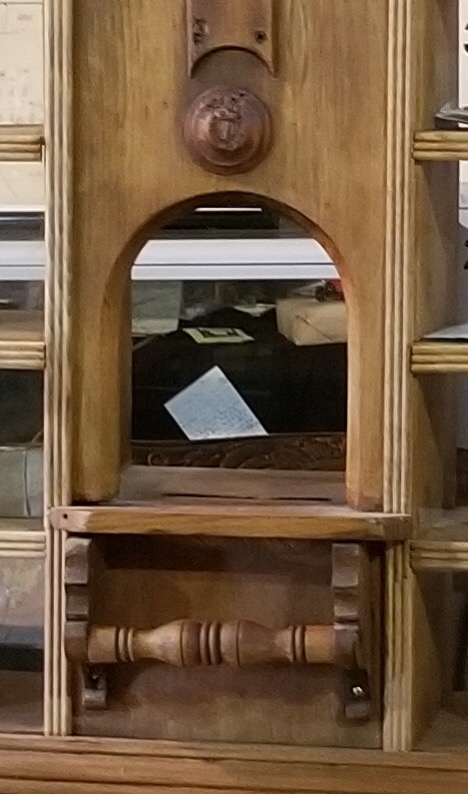

The mail sorter was the forerunner of today’s post office box system. Whereas today people can whip into the post office with key in hand and quickly get their mail from their P.O. Box, in earlier times the mail was sorted into numbered, glass fronted boxes nestled together in a cabinet mounted one a table. The postal clerk or, in most places the size of Coldwater, the postmaster stood behind the table and handed you the mail from your numbered box. This meant that on occasion you would find yourself in line while another ahead of you may engage the postmaster in idle gossip. Customer: “Well…I heard…the cherry pie Mary Chater entered in the Fall Fair came from Walker’s bakery. And it won second prize!” Postmaster: “Perhaps Walkers might henceforth want to advertise their pies as prize-winning.” “NEXT!” But I digress.

That winter we restored our new gem. Bob remembers how a visit to a car wash solved the issues of some layers of crud. The next step required a level of dexterity since much of the finer pieces – the ones that were not already missing – had to be detached. Replacements for the missing and damaged pieces needed to be fabricated. John worked some serious magic by hand-carving a couple of rosettes. He also produced a long piece of scrollwork that crowns the front of the sorter. All the glass was replaces. Trip around the boxes posted a challenge. A few lengths of a closely matched moulding were the ticked. These we cut, fitted and attached to the glass with double-sided adhesive strips.

The completed assembly required sanding with two grades of fine sandpaper. Providing a finish that is close to the original colour required the mastery of our two most experienced antique refinishers, Mike and Bob. Mike grew up in a family of “antiquophiles.” When I asked him about the formula for the final coats of finish he said, “If I tell you, Clay, I’ll have to kill you! It’s a secret family recipe that my mother got a long time ago from a farmer in Trois Rivieres.” All I was able to determine is that it consisted of a highly flammable mixture of linseed oil, beeswax and turpentine in approximately equal portions. Apparently, the secret lies in the manner in which the elements are “cooked.” Two coats of this unique finish were buffed on with soft cotton cloths. Minwax stain was added to the mix when applied to the newer pieces to get a good colour match.

The final step of the process was numbering the glass fronts of the 54 boxes. This assignment was given to me, the very armature artist. Numbers, letters and sign painting not being in my wheelhouse, a trip to Staples was in order. There I obtained several sheets of peel and sticks decals that were relatively easy to apply. Voila! And very professional looking, I might add!

While we were busy at Gary’s shop, our honorary A-Team member, Rollie produced in his home workshop the elegant able upon which our mail sorter so proudly rests – the dilapidated table that had accompanied it was neither original nor salvageable. Therewith we were able to install the completed ensemble making it the focal point of the village post office on Main Street in the display barn at CCHM.

And now, dear reader, we have a problem and we need your help. Ad mid-point of the sorter and at the table level there is an opening for the pass through across the table of mail stamps, money, etc. It has a door the postal clerk can raise and lower as required. That is clear enough. However, there is also in that vicinity a turned rod about an inch and a half in diameter mounted between two protruding brackets. At approximately sic inches long it looks similar to the core of a toilet roller and is accessible from the front only. And it doesn’t rotate, but is locked in place with no apparent means of release. We are done stratchin’ our heads! Somebody Tell us what it is, and what is its purpose! PUH…lease!

If you are are retired – or not – and want to spend one day a week with a group of really great guys doing some remarkable historical preservation works, give me a call at (705) 209-1087. Or email me at clayyoung695@gmail.com.